Although the black communities of the San Juan Community Council fear that the dispossession of at least 32,000 hectares of their territory will materialize due to the movement of an international business network, these companies were not by any means the first owners. Before reaching them, they passed through several hands that, apparently, simulated the legality of an irregular title.

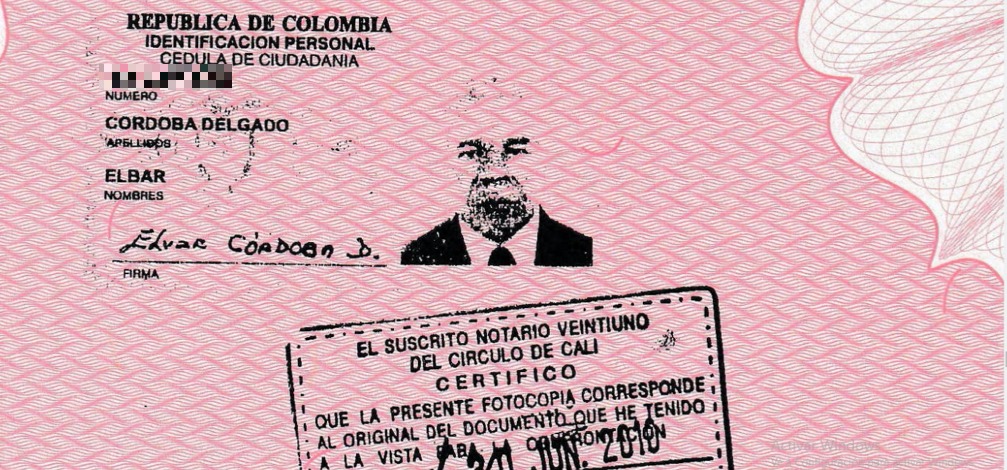

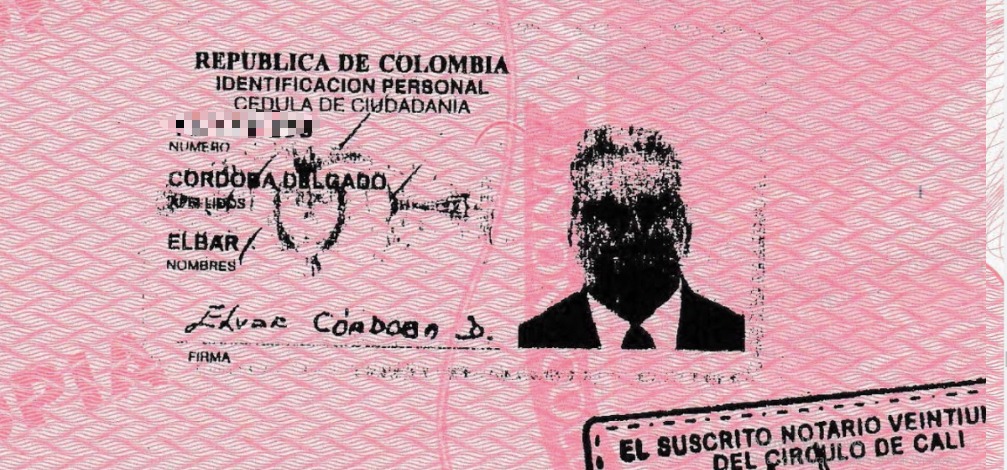

On February 10th, 1990, the Colombian Institute of Agrarian Reform (Incora) allegedly issued Resolution 01326, through which it titled 32,450 hectares in the deep jungles of the southern department of Chocó, in defiance of the regulations in force at the time, which limited this type of decision to only 450 hectares. The beneficiary was Elvar Córdoba Delgado, a native of the municipality of Yumbo, in Valle del Cauca.

The extension of this property, which has great natural wealth, is of 32,450 hectares, larger than the surface of a country like Malta and larger than at least 500 Colombian municipalities. It is located, according to documents consulted, on the "eastern side downstream of the Garrapatas River, Serranía de los Paraguas, in the municipality of Sipí in the department of Chocó".

This large amount of land overlaps with the collective title of the General Community Council of San Juan (Acadesan), a circumstance that worries the inhabitants of the black communities settled in Sipí because they fear that their ancestral territory will be cut off.

A review of the certificate of tradition and freedom registered in the Superintendence of Notaries and Registry under the real estate registration number of 184-9929, shows that this alleged adjudication was duly registered, but 15 years after its occurrence, which raises doubts about its legality.

But this is not the only concern. When looking for this adjudication in the inventory of requests for land titles, it does not appear registered, as if the agrarian authority had never made that decision, although this administrative act is recognized by the National Land Agency (ANT) and this was made known to this portal after consulting this case.

Defying all laws

Regarding the alleged date of adjudication, Law 135 of 1961, on agrarian social reform was in force, through which it was intended to eliminate and prevent the inequitable concentration of rural property or its uneconomic division and to provide land "to those who do not own it"Article 29th, "on the Nation's uncultivated lands", specifies that they could only be awarded by "prior occupation and in favor of natural persons or peasant cooperatives or community enterprises".

This norm also specified that the size of the land to be allocated could not exceed 450 hectares per "person or per member of the community enterprise or peasant cooperative". The specification for natural persons could make the adjudication greater if it was alleged that they were "located in very remote regions", but, in any case, the maximum stipulated was of 1,000 hectares.

Not to mention that regions such as southern Chocó were considered a Protected Forest Zone, in application of Law 2 of 1959, which regulates the forestry economy of the Nation and conserves natural resources. For this reason, in principle, land should not have been titled to natural persons in Sipí and its surroundings.

The date of adjudication is also a cause for concern. It was not until 1993, with Law 70, that the route for collective titling for the black communities was defined; and it was only in 2001 that the General Community Council of San Juan (Acadesan) achieved collective titling before the Incora. Although the adjudication apparently took place in 1990, by which time no black community had collective title to their lands, the communities of San Juan were already organized and had inhabited these territories for a long time.

And if we’re talking about ownership, the 32,450 hectares awarded not only affect the territory of the black communities of Sipí, but also, to a lesser degree, the Río Garrapatas indigenous reservation of the Embera Chamí people. In this respect, Law 135 specifies that "no land that is occupied by indigenous communities or that constitutes their habitat may be adjudicated, but only for the constitution of indigenous reserves".

If this adjudication is true, Incora was not aware of the fact that since March 26th, 1980, through Resolution 021, this territory was constituted as an indigenous reserve, which was subsequently formalized as a reservation on June 1st, 1987 through Resolution 043.

A complete stranger

For the black communities of Sipí, the name of Elvar Córdoba Delgado is unknown both in the municipal capital and in the villages of Tanando, Santa Rosa and Marquesa, close to the adjudicated land. Sources consulted by this portal affirmed that they had never before heard of the adjudicator and much less recognize that any landowner from Valle del Cauca worked so much land in that region.

This lack of recognition is not minor, since one of the conditions required by Law 135 of 1961 is that in addition to occupying the land, the grantee must economically exploit two thirds of the area of the land requested from Incora. However, the community maintains that the reality is different. "Not even the surnames are from our territory", says Elizabeth Moreno Barco, also known as 'Chava', legal representative of Acadesan's Major Council.

Is this an irregular process? The indication seems to lead to a yes. And there are even more suspicions. At the time of the adjudication, John Jairo Arcila Ramírez was the regional manager of Incora in Cali. Years later he was prosecuted and convicted, along with other members of that office, for carrying out an irregular process of awarding fallows.

That case has points in common with the alleged land adjudication in Sipí. According to file 14981 of 1998, the office that Arcila headed granted a plot of land in violation of the due process for the adjudication of vacant land, as contemplated in Decree 2275 of 1988. In view of these irregularities, Incora took the land away from those who had received it in an irregular manner and legal proceedings were initiated against the public officials of Incora's Cali regional office who were involved in the criminal acts.

Due to these facts, Arcila and some of the entity's lawyers were prosecuted, most notably Constanza Medina Chaparro, who in the resolution that favored Córdoba appears signing in the"Registration Data" field of the adjudication. In sum, at least two of the signatories appearing in the certificate of adjudication of the 32,450 hectares claimed by Acadesan, faced a criminal sanction for an illegitimate process of adjudication of uncultivated land.

Through the cross-checking of various sources of information, this portal established that the file in the possession of the ANT is missing several documents pertaining to the procedure for the adjudication of vacant land, including a copy of the adjudication request, the plans of the property and a copy of the gazette or official gazette in which the administrative decision was to be registered, which would indicate possible illegal actions in the process.

Irregular registration?

Another fact that raises suspicions about the validity of this award is the delay in registering the resolution with the Public Instruments Registry Office of the municipality of Istmina, which has jurisdiction over Sipí. The registration was made on March 31st, 2005, that is, 15 years after the alleged resolution was issued by Incora.

The legal team supporting Acadesan in this process wonders why wait so many years to register that amount of land. To resolve that doubt, VerdadAbierta.com tried to contact Elvar Córdoba through the contact means registered in the deeds he signed, but there was no answer in all the telephones there found.

In addition to the delay in the registration, a review of the certificate of tradition and freedom that the system of the Superintendence of Notaries and Registry shows generates another concern that casts doubt on the legality of this titling. This time it has to do with the cadastral number of the property.

Until 2012, the Public Registry Offices assigned a 20-digit cadastral code. This number establishes several characteristics of the registered property, including its location by department and municipality. When observing a current certificate of tradition and freedom, under which the 32,450 hectares property was registered, an irregular cadastral code stands out as it only has 19 digits and would correspond to a property in a municipality of Boyacá that does not exist.

With the implementation in 2013 of the National Property Number (NPN), adopted by the Agustín Codazzi Geographic Institute (IGAC) to identify urban and rural properties, the code was increased to 30 digits that included information from Cadastre, and Notary and Registry. Thus, the property claimed by Acadesan changed its cadastral code and this time it was located in Sipí. This is how the registration acquired a legal formalism, but it still does not exist in the cadastre databases.

VerdadAbierta.com consulted with the Superintendence of Notaries and Registry (SNR) about the possible reasons for this change in the cadastral code. In a first explanation, Andrea Caterine Mora Silva, Coordinator of the Interoperability Group of the Multipurpose Cadastre Registry, stated that, indeed, the code from before 2013 "does not allow the identification at the cadastral level of the real estate in the municipality of Sipí, in the department of Chocó".

And in a second explanation as to why these types of errors occurred, the official responded that "they may be associated to how the registration of the previous and new cadastral numbers was handled, because the information of the previous cadastral code contained in the real estate registration folios was registered in the folio by the respective appraiser from a cadastral certificate or the identification of the cadastral or property number or code consigned or referred to in a public deed".

The SNR was also asked who was in charge of the Public Instruments Registry Office of Istmina in 2005. According to the entity's press office, the sectional registrar was Gentil Iván Díaz, now deceased.

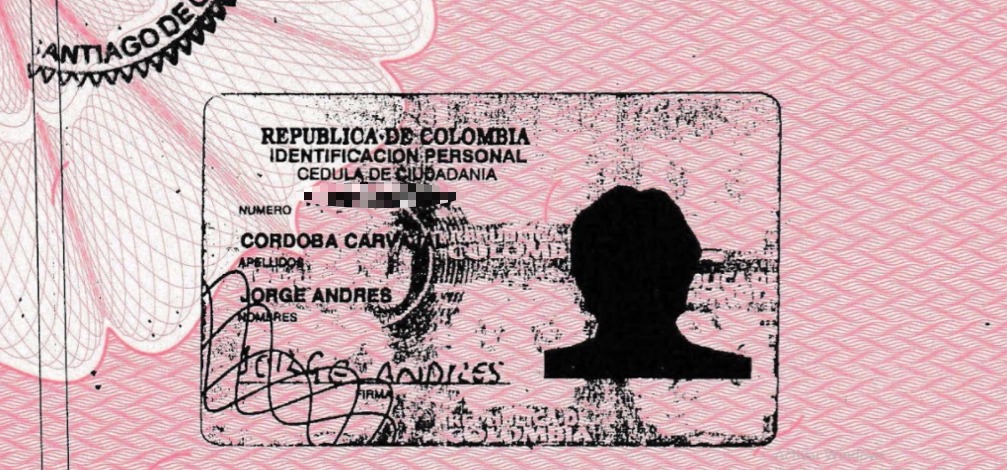

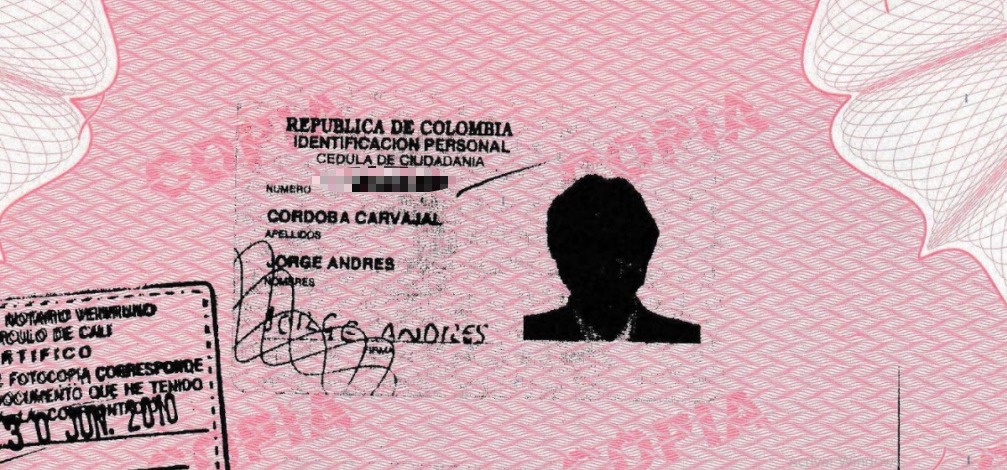

In 2008 this property was sold by Córdoba to Evelio Arias Marín and Jorge Andrés Córdoba Carvajal. The deal was recorded in public deed 4153 of October 23rd of that year before the 21st Notary Office of the city of Cali. The particularity of this business is the sale price: 5 million pesos, that is, for each hectare 154 pesos were paid (not even a cent on the dollar), a figure that also raises many doubts about the legality of this real estate transaction.

When asked about the new owners of the land, some of the residents of the communities located near the Garrapatas River, they responded that they had never heard of them.

VerdadAbierta.com attempted to contact Arias and Córdoba through the cell phone numbers registered in documents related to the business but did not receive a response.

Suspicious company appears

These new owners would make the deal of a lifetime five years later, when they sold the 32,450 hectares property to a company then called Desarrollo e Inversiones Progreso Verde S.A.S, represented by Luis Enrique Betancur Hernández. On this occasion, the transaction was registered in the 28th Notary Office of Bogota through public deed 1142, dated June 26th, of 2013.

Initially, the sale was agreed for 3.4 million dollars, equivalent to 6,556 million pesos according to the rate in effect on the day of the deal, and this was recorded in the property's certificate of title. But the documents show that 446 million pesos were paid. Why this variation in the price of the land?

It turns out that Arias and Córdoba promised to deliver a complete and authenticated copy of the 32,450 hectares adjudication file, which the agrarian authority of the time, the Colombian Institute for Rural Development (Incoder), should’ve of had, and a document signed by the black authorities of Acadesan in which they acknowledged the existence of a private land within their collective territory. But the sellers did not show up with either one or the other.

"I remember that there was a settlement because they could not fulfill anything that was agreed in the original deed. But they did get paid a good cut", recalls Betancur, who was contacted by this portal in East Timor, where he provides his services to the government of that Southeast Asian country on environmental issues.

The public deed in the possession of VerdadAbierta.com shows that as part of these payments to the sellers, the company Desarrollo e Inversiones Progreso Verde wrote two management checks: one for 111 million 440 thousand 095 pesos in the name of Marcela García Ocampo; and another for 100 million pesos to Sandra Milena Vélez, both dated June 26, 2013. It is not known in whose name the remaining money was drawn.

In the face of these defaults, when asked if he or the company remained in contact with the former owners, Betancur said they never spoke again. "They took their checks and disappeared off the map", he maintained.

However, a clause was included in the deed in this respect, with which they intended to free themselves from any liability to other occupants: "The SELLERS declare and guarantee that: (i) There is no communal possession or ownership of the property being sold by ethnic groups, or that it has the legal character of an indigenous reservation, and that the property being sold is entirely privately owned and therefore is excluded from any title or right of third parties, particularly of the COMMUNITY COUNCIL ACADESAN, constituted by Resolution 2702 of December 21st, 2001, issued by INCODER (sic) and of the RESGUARDO, INDIGENOUS SANANDOCITO, belonging to the ETNIA EMBERRA (sic) KATIO constituted by Resolution N° 0008 of February 20th, 2001".

The business of the 32,450 hectares of land in Sipí was counselled by the firm Salazar & Asociados Abogados, which specializes in representing companies in commercial and tax law matters, including Desarrollo e Inversiones Progreso Verde in its incorporation.

VerdadAbierta.com contacted Juan Carlos Salazar, director of Salazar & Asociados Abogados, to understand how the business deal that the black communities of southern Chocó are questioning was made. In this regard, he explains that Laura Romero, an external lawyer of the firm, was hired to evaluate the viability of the purchase. She reviewed the documents provided by the sellers and asked Incoder for the process file, but it wasn’t given to her. The findings were included in a report that the firm delivered to the directors of Desarrollo e Inversiones Progreso Verde, who finally made the decision to purchase the land and Betancur, as legal representative, notarized the deal.

“As far as they showed us, things looked in order from the top", Salazar explains. “They showed me a certificate of freedom from the Registry Office, I go, I ask them to certify if it’s original, that it’s okay, I ask for another one from the Registry Office and everything checks out. I ask for the cadastral registry and they give me a cadastral registry of the municipality. That is to say, the things that could be checked in the short time we had, were checked and what could not be checked, which they —the sellers— said was checked, we asked them to leave it under oath”.

In the hands of entrepreneurs

On July 22nd, 2016, a new transaction on the 32,450 hectares property was formalized before Notary 20 of Bogota, which was recorded in public deed 1000. This time Desarrollo e Inversiones Progreso Verde SAS sold the land to Proyecto Horizontes Verdes SAS, for 988 million pesos. For that year, both companies had the same legal representative: Canadian citizen Marc Robert Williams, one of the foreign businessmen allegedly involved with the companies that control the Colombian companies.

In the deed through which this purchase and sale was registered, a note of clarification was included that draws attention: "The participants state to the Notary that the property subject of this purchase and sale is not located in an area of high risk or forced displacement", which contrasts with reality, since, historically, the communities of San Juan, and specifically those of Sipí, have been victims of uprooting due to the armed conflict.

In fact, seven months before that deal, the Early Warning System of the Ombudsman's Office warned of the risk faced by urban and rural communities in the municipalities of Istmina, Medio San Juan and Sipí due to the presence of illegal armed groups interested in drug trafficking and criminal mining activities.

According to this warning, this confluence of actors "has increased pressure on ethnic authorities and organizations, which prevents the development of traditional subsistence production activities. This situation is aggravated because the State has not efficiently exercised control over natural resources, monitoring of environmental impact measures, and water protection".

The last notification of the certificate of tradition and freedom was formalized with public deed 1484, dated August 23rd, 2018 at Notary Office 65 of Bogota. What was done on that occasion was to register the change of name of the property from "Baldío" to "Horizonte Verde".

Today, at least on paper, these 32,450 hectares belong to the firm Eightfold Biodiversity Bank SAS, formerly known as Proyecto Horizontes Verdes SAS, which, according to some documents consulted, is dedicated to investing in companies and real estate and personal property.

What is still not clear to the black communities of the Acadesan community council is what these 32,450 hectares were purchased for. The inhabitants were told that ecotourism and environmental projects would be developed, but they believe that this is just a façade.